Honoured with 2015 Prize for Freedom

The Chairman of CDPB has been presented with the 2015 Liberal International, Prize for Freedom, by LI President, Dr Juli Minoves, at a ceremony in Zurich in June in the presence of many liberal politicians from around the world.

The annual Prize for Freedom is Liberal International’s highest recognition and has been awarded each year since 1985 to an individual who is seen as having made “an exceptional contribution to the advancement of Human Rights and Political Freedom”.

Previous laureates of the Prize for Freedom have come from across the world and have included, Helen Suzman, Aung San Suu Kyi, President Mary Robinson, President Vaclav Havel, Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, Hans-Dietrich Genscher and President Corazon Aquino. The first recipient in 1985 was former Argentinian President, Raul Alfonsin for his various contributions to peace in South America.

The nomination for the 2015 Prize for Freedom came from the German Group of Liberal International which cited “Lord Alderdice’s contribution to negotiating the Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland and his participation in peace missions around the world….work which continues particularly through his Directorship of the Centre for the Resolution of Intractable Conflict, based at Harris Manchester College, University of Oxford”.

Eva Grosman talks TEDxStormontWomen

NI Business Now spoke to Eva Grosman, Chief Executive of the Centre for Democracy and Peace Building, ahead of the TEDxStormontWomen event which will take place in Belfast later this month.

Describe your daily role:

By working with people in other areas of conflict we hope to contribute to rekindling momentum in the Peace Process and by linking with partners in political and civil society here, bring some fresh approaches to understanding conflict and addressing the legacy problems which still stand in the way of a stable, shared and inclusive society.

A think-tank component of the Centre’s activities is developed through collaboration with local academic institutions and with Oxford, Harvard and other universities. The Centre also promotes local initiatives and campaigns, such as ‘Unite Against Hate’ – a programme challenging prejudice and hate crime.

What is the best part of your job?

I work with fantastic individuals, who share similar values and vision of building a better future for the next generations, here in Northern Ireland and beyond. My job allows me to travel, to work with people from different backgrounds and cultures. I also enjoy the freedom, flexibility and independence.

Outside of your 9-5 you work on another project – tell me about that?

Yes, I’m an organiser and curator of TEDxStormont events. I’m a massive fan of TED. It is a great way to get inspired, to explore interesting concepts and to connect with people and ideas from across the globe.

What led you to start this?

I was also lucky enough to attend the TED Global conference few years ago and meet Chris Anderson, Head of TED and Bruno Giussani, European Director of TED. I applied for a free TEDx licence while working on Politics Plus at the Northern Ireland Assembly. I thought it would be an excellent way of becoming a part of the global conversation.

What events are in the pipeline?

I’m currently curating TEDxStormontWomen event, which is part of TEDWomen 2015 that focuses on women and women’s issues. The overall theme is “Momentum. Moving forward. Gaining speed. Building traction”. We’ll explore some bold ideas that create momentum in how we think, live and work. Our event is one of many TEDx events happening around the globe. It will include 10 live speakers/performers and we will also stream videos from TEDWomen in Monterey, California (including talks by Mary Robinson, Jimmy Carter and many others). The event will take place in Stormont Castle on Friday, 29 May from 2pm to 5.30pm followed by the networking reception from 5.30pm to 7pm.

How do you manage to find the time to accomplish so much?

It is all about good time management and delegation. And of course being passionate about what you do and having fun, too.

What has been your biggest achievement to date?

One of the extra special achievements was definitely Gary Lightbody’s support for TEDxStormont. I had e-mailed him about getting involved – not only did he agree to speak at our event, he also wrote a song, which he performed with a younger generation of Northern Ireland finest musicians, including SOAK, David C Clements, Silhouette and the Wonder Villains. He then donated all proceeds from the record sales to the Northern Ireland Music Therapy Fund. Gary often speaks of the invisible tribe – organising TEDx is like bringing the invisible tribe together.

What is your goal for the year ahead?

I want to continue to spark exciting conversation, to reach out to wider audiences, to inspire future generations and attract TED Global to Belfast in the near future.

If you had to give one piece of business/life advice, what would it be?

Work hard, do some good and have fun!

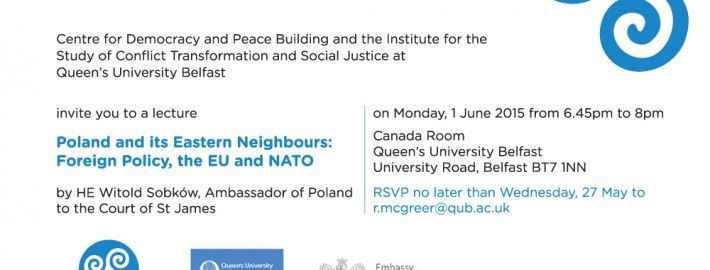

Poland and its Eastern Neighbours: Foreign Policy, the EU and NATO

Centre for Democracy and Peace Building and the Institute for the Study of Conflict Transformation and Social Justice at Queen’s University Belfast

invite you to a lecture

Poland and its Eastern Neighbours: Foreign Policy, the EU and NATO

by HE Witold Sobków, Ambassador of Poland to the Court of St James

on Monday, 1 June 2015 from 6.45pm to 8pm

Canada Room, Queens University Belfast, University Road, Belfast BT7 1NN

RSVP no later than Wednesday, 27 May to r.mcgreer@qub.ac.uk

________________

Until his appointment as Ambassador of Poland to the Court of St. James’s in August 2012, Witold Sobków served as Permanent Representative of Poland to the United Nations in New York and as Political Director (CFSP). Previously, he was in the Department of Strategy and Planning of Poland’s Foreign Policy, with the rank of Titular Ambassador. In 2006 he served as Under-Secretary of State for European Affairs.

Witold Sobków was Poland’s Ambassador to Ireland from 2002 until 2006, prior to which he had been Senior Adviser to the Minister on European Affairs. In

2001 he was Director for Non-European Countries and the United Nations System, having served as Deputy Head of the West European Department since November 2000 when he came back from the UK having acted as Deputy Head of Mission at the Polish Embassy. Before joining the Ministry, Witold Sobków was for 7 years a lecturer at Warsaw University.

He is a civil servant and holds two MAs /summa cum laude/ in English language and literature, and in Italian language and literature, both from Warsaw University. He undertook various postgraduate programmes, e.g. Islamic studies at London University, security in South-East Asia at King’s College, diplomacy/economics/security/political science at Stanford University as well as national and international security at Harvard. He received scholarships to study in Siena, Venice and Perugia.

We cannot begin to tackle hate crime and bigotry without a shared vision

A young Lithuanian woman has been left to pick up the pieces of her business – a nail bar in east Belfast – following a racially-motivated arson attack, which left the small business burnt to the ground.

This sickening attack follows on the heels of incidents in north Belfast, where Polish residents were targeted because of their race.

A few days ago, the local media reported a 43% increase in hate-related crime incidents, following the attacks on members of the Polish community; it went almost unnoticed.

During his first historic visit to Northern Ireland the then US President Bill Clinton said: “Countries are just like people with their personalities, hopes and nightmares.”

So, using his analogy, I tried to imagine Northern Ireland as a person – an insecure teenager, rather aggressive on occasions, who finds it extremely difficult to take responsibility for his own actions and is constantly blaming others. He is spoiled rotten by the rich uncles in London and an older, not rich, aunt in Dublin. He is driven, fun-loving with a great sense of humour. He even shows major potential, yet he is still unsure about his own identity, worth and future.

The question I have now is this: as a society attempting to evolve from the dark days of the Troubles into a more multi-cultural country, how can we try to mature together? We cannot begin to address hate crime, bigotry and other social problems here without a vision or a shared sense of commonality. Differences are important, but common humanity matters more.

The problem is in Northern Ireland so much is fragmented. There is so much talk about “multi-agency approach” involving strategies and action plans, but it seems that very little progress is being made. I suppose it’s part of our fledgling society which is still trying to grow up.

Perhaps we all need to take a leaf out of President Clinton’s book. He did not talk about the old, bureaucratic and mediocre networks, but a new, creative approach to leadership.

We need a new approach if we want an inclusive society here. The world is changing – and so, too, is Northern Ireland.

Together, perhaps, we can turn the immature teenager into a tolerant and responsible grown-up.

Expert led hate crime conference expected to outline a ‘better future’ for Belfast

The key issue being explored by a range of partners at the ‘Towards A Better Future’ Conference taking place at Belfast City Hall today is how to make a positive impact on hate crime and promote Belfast and Northern Ireland as a place confident in the benefits of diversity.

Led by the Belfast Policing and Community Safety Partnership in association with the Centre for Democracy and Peace Building and supported by Unite Against Hate, Department of Justice, and Belfast City Council, the conference will play an important role in facilitating a citywide and regional conversation to promote social cohesion and tolerance.

Set against a backdrop of rising levels of hate crime and in particular levels of racist hate crime in Belfast, the focus of the conference will be to further develop the short/medium term work already underway and to begin the process of exploring how shared outcomes can be achieved.

The conference kicks off with a range of leading specialists in the field of hate crime and social cohesion sharing knowledge and expertise. There will then be sessions in different locations across the city, where delegates have the opportunity to engage directly with communities on how hate crime and intolerance affects them.

As part of these satellite sessions, Belfast and Northern Ireland will also have the opportunity to showcase its existing good practice with a wide and varied range of related case study presentations.

The final conference session will work with all delegates to develop an agreed platform for action going forward and the overall conference report will link to the development of “The Belfast Agenda” which is Belfast’s Community Plan.

Cllr Colin Keenan, Chairman Belfast Policing and Community Safety Partnership said today:

“The ‘Towards A Better Future’ conference will, in my opinion, be the start of a new era of tolerance and respect in our City and across our region”.

“Many immigrants come to Northern Ireland for work and the chance of a better life. That’s why it’s imperative that we, in positions of responsibility, make it our business to make them feel welcomed”.

“This conference will build on the great work of the Centre for Democracy and Peace Building, Queens University Belfast and Belfast PCSP, who jointly published a report dispelling common myths surrounding immigrants in our city.”

“On that point I want to thank all involved in this conference and praise them for their work. Together we can build a better future for everyone”.

Justice Minister David Ford MLA added:

“There is a responsibility on all of us to work towards a truly shared and inclusive society. My Department’s Community Safety Strategy recognises that a growing diverse society can bring challenges in how some people perceive a problem and react to it. If unchallenged, prejudices can grow and negative attitudes can be learned. These can manifest into abuse; intimidation; damage to property; and unfortunately physical injury.

It is important that we all unite in the message that hate and intolerance are not acceptable and that the society we aspire to is one which promotes equality and will challenge prejudices. I believe that reducing prejudicial attitudes driving hate is achievable but requires strong leadership and partnership working across the justice agencies, Executive Departments, local government and the broader voluntary and community sector. I therefore welcome today’s conference which makes a valuable contribution to that debate.”

Lord John Alderdice, Chairman of the Centre for Democracy and Peace Building added:

“The ‘Towards a Better Future’ conference aims to build on the excellent work already undertaken in Belfast and across the region to tackle prejudice and promote social cohesion. Bringing together the right mix of people, at the right time via a number of dynamic sessions we aim to promote wider knowledge of the issues and how to equip policy makers and those tasked with implementation through examples of good practice.”

PSNI Assistant Chief Constable Stephen Martin said:

“We take hate crime very seriously and actively investigate all incidents reported to us. Hate crime is wrong on all levels and the PSNI will do everything it can to protect and reassure the growing number of people from different backgrounds and cultures who choose to come to Northern Ireland to live, work or study. We know this type of crime can have a devastating effect on victims and we want to reassure everyone that we are committed to tackling this issue and playing our role in preventing these crimes occurring.”

In May last year we launched Operation Reiner, a co-ordinated investigation into a series of hate crimes across Belfast. Since then we have made 95 arrests and 46 have been charged. As this work continues – the message is clear – Actions have consequences. If you choose to demonstrate your hatred by attacking or abusing others we will investigate you and seek to bring you to justice.”

This conference provides a great opportunity to collectively look at what we can do together to tackle hate crime. Police alone cannot provide a solution. It requires a long-term, collective multi-agency response with the range of skills and perspectives necessary to build a safer, more confident society which welcomes diversity. By building strong partnerships empowered and capable to address the identified issues, we can start to get to the heart of the problem, providing long lasting solutions which increase awareness and confidence in all communities.”

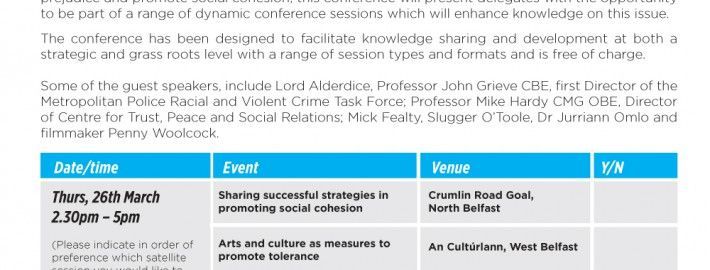

Towards A Better Future

Belfast Policing and Community Safety Partnership (PCSP) and the Centre for Democracy and Peace Building are delighted to invite you to participate in:

“Towards a Better Future: Hate Crime and Community Cohesion Conference”

Building on the excellent work already undertaken in Belfast and across the region to tackle prejudice and promote social cohesion, this conference will present delegates with the opportunity to be part of a range of dynamic conference sessions which will enhance knowledge on this issue.

The conference has been designed to facilitate knowledge sharing and development at both a strategic and grass roots level with a range of session types and formats and is free of charge.

For more information please contact Katharine McCrum at mccrumk@belfastcity.gov.uk or by telephone on 02890270556.