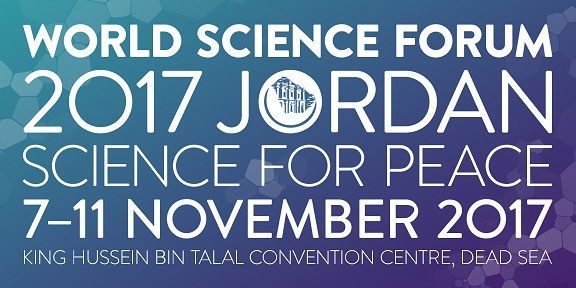

Thanks to the invitation from the Global Thinkers Forum, the Centre for Democracy and Peace Building is delighted to partner with the WANA Institute and host the session at the World Science Forum in Jordan.

World Science Forum 2O17 theme is Science for Peace. It will engage the world of science and redefine the global potential of scientific communities and policymakers to bring real change to our interlinked societies.

CDPB is delighted to co-curate and participate in the Emerging Concerns in Managing Radicalisation among Youth session.

Current geo-political challenges in the Middle East impact how researchers and policy makers can manage radicalisation among youth. New forms of extremism are likely to re-emerge despite the military defeat of Daesh, particularly that the political and socio-economic structures and ideologies that contributed to the phenomenon remain intact in the region. Recent developments in Europe also point to an increase in radical lone wolves compared to earlier threats of organised armed groups. These challenges raise important question into best approaches to manage radicalisation as a spiritual-ideological quest, and as a response to structural frustrations.

This session draws on multi-disciplinary research in Europe and the Middle East with insight from field research with fighters and returnees to addresses crucial questions like:

• How does the spiritual factor enhance or undermine CVE efforts? How the spiritual interacts with the structural in understanding radicalisation and necessary CVE efforts?

• How can policy makers and CVE stakeholders introduce behavioural and ideological transformations that can delegitimise extremist ideologies?

• What are the prospects and challenges for reintegrating returnees in local communities with the current legal and communal infrastructure?

• How can current knowledge and practices on CVE be revised and re-designed for efficient preventive CVE measures?

Dr Dalia Ghanem-Yazbeck, El Erian Fellow, The Carnegie Middle East Center (CMEC), Beirut, will moderate the panel discussion.

Speakers:

Dr Neven Bondokji, West Asia North Africa Institute

Eva Grosman, Centre for Democracy and Peace Building

Professor Mike Hardy, Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations, Coventry University

Amin Nehme, Lebanese Development Network

The session will take place on Friday, November 10 at 11.30am.