The key issue being explored by a range of partners at the ‘Towards A Better Future’ Conference taking place at Belfast City Hall today is how to make a positive impact on hate crime and promote Belfast and Northern Ireland as a place confident in the benefits of diversity.

Led by the Belfast Policing and Community Safety Partnership in association with the Centre for Democracy and Peace Building and supported by Unite Against Hate, Department of Justice, and Belfast City Council, the conference will play an important role in facilitating a citywide and regional conversation to promote social cohesion and tolerance.

Set against a backdrop of rising levels of hate crime and in particular levels of racist hate crime in Belfast, the focus of the conference will be to further develop the short/medium term work already underway and to begin the process of exploring how shared outcomes can be achieved.

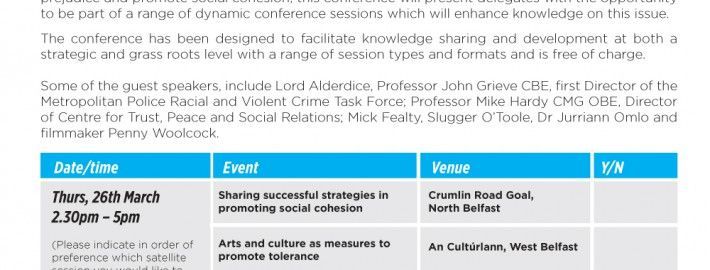

The conference kicks off with a range of leading specialists in the field of hate crime and social cohesion sharing knowledge and expertise. There will then be sessions in different locations across the city, where delegates have the opportunity to engage directly with communities on how hate crime and intolerance affects them.

As part of these satellite sessions, Belfast and Northern Ireland will also have the opportunity to showcase its existing good practice with a wide and varied range of related case study presentations.

The final conference session will work with all delegates to develop an agreed platform for action going forward and the overall conference report will link to the development of “The Belfast Agenda” which is Belfast’s Community Plan.

Cllr Colin Keenan, Chairman Belfast Policing and Community Safety Partnership said today:

“The ‘Towards A Better Future’ conference will, in my opinion, be the start of a new era of tolerance and respect in our City and across our region”.

“Many immigrants come to Northern Ireland for work and the chance of a better life. That’s why it’s imperative that we, in positions of responsibility, make it our business to make them feel welcomed”.

“This conference will build on the great work of the Centre for Democracy and Peace Building, Queens University Belfast and Belfast PCSP, who jointly published a report dispelling common myths surrounding immigrants in our city.”

“On that point I want to thank all involved in this conference and praise them for their work. Together we can build a better future for everyone”.

Justice Minister David Ford MLA added:

“There is a responsibility on all of us to work towards a truly shared and inclusive society. My Department’s Community Safety Strategy recognises that a growing diverse society can bring challenges in how some people perceive a problem and react to it. If unchallenged, prejudices can grow and negative attitudes can be learned. These can manifest into abuse; intimidation; damage to property; and unfortunately physical injury.

It is important that we all unite in the message that hate and intolerance are not acceptable and that the society we aspire to is one which promotes equality and will challenge prejudices. I believe that reducing prejudicial attitudes driving hate is achievable but requires strong leadership and partnership working across the justice agencies, Executive Departments, local government and the broader voluntary and community sector. I therefore welcome today’s conference which makes a valuable contribution to that debate.”

Lord John Alderdice, Chairman of the Centre for Democracy and Peace Building added:

“The ‘Towards a Better Future’ conference aims to build on the excellent work already undertaken in Belfast and across the region to tackle prejudice and promote social cohesion. Bringing together the right mix of people, at the right time via a number of dynamic sessions we aim to promote wider knowledge of the issues and how to equip policy makers and those tasked with implementation through examples of good practice.”

PSNI Assistant Chief Constable Stephen Martin said:

“We take hate crime very seriously and actively investigate all incidents reported to us. Hate crime is wrong on all levels and the PSNI will do everything it can to protect and reassure the growing number of people from different backgrounds and cultures who choose to come to Northern Ireland to live, work or study. We know this type of crime can have a devastating effect on victims and we want to reassure everyone that we are committed to tackling this issue and playing our role in preventing these crimes occurring.”

In May last year we launched Operation Reiner, a co-ordinated investigation into a series of hate crimes across Belfast. Since then we have made 95 arrests and 46 have been charged. As this work continues – the message is clear – Actions have consequences. If you choose to demonstrate your hatred by attacking or abusing others we will investigate you and seek to bring you to justice.”

This conference provides a great opportunity to collectively look at what we can do together to tackle hate crime. Police alone cannot provide a solution. It requires a long-term, collective multi-agency response with the range of skills and perspectives necessary to build a safer, more confident society which welcomes diversity. By building strong partnerships empowered and capable to address the identified issues, we can start to get to the heart of the problem, providing long lasting solutions which increase awareness and confidence in all communities.”